In the first part of our interview with triathlon supercoach Jack Maitland, we looked back on his sporting background as an elite athlete across several sports, which ultimately lead him to representing Scotland and Great Britain in international competition through the 1990’s.

Without planning it, that history formed the start of his now 21 years (and counting) career as a full-time triathlon coach.

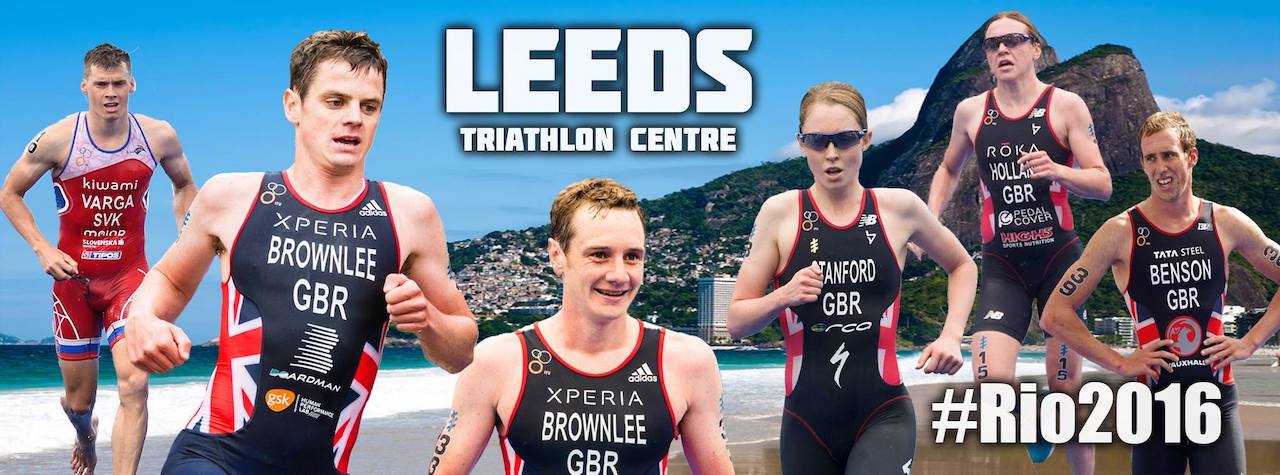

For those in the UK and indeed beyond, the Leeds Triathlon Centre is renowned for developing athletes including the Brownlee brothers, Vicky Holland, Non Stanford et al. Not only was Jack the Head Coach for 13 years, but he was instrumental in its very existence.

So how did the story begin?

So, how was the Leeds Centre even formed?

“Simon Ward and I were running this Junior squad, mostly aged 14-18; we were happy with what we were doing, but we were seeing that people were leaving our region to go to university. Really, the only university catering for that level of development athlete then was Loughborough. There was a Senior squad at Bath, but basically we were losing athletes out of our region and our squad.

“We thought we could support a university programme here, that Leeds could do it as we’ve got good universities and facilities. We were promoting and pushing that idea, firstly with British Triathlon, which was fairly well received by the Performance Director at the time, Graeme Maw.

“We were also sounding out the universities at the same time, and by lucky coincidence, Malcolm Brown became the Head of Sport at Leeds Metropolitan University, now Leeds Beckett. I didn’t know Malcolm at all at the time; I knew there was a Malcolm Brown who was the UK Athletics Endurance Coach, but I wasn’t at all sure it was the same Malcolm that I knew had been at Edinburgh University and Head of Sport there.

“Anyway, I managed to get my feet under his desk in the first week of his job for a meeting and gave him my hard sell for a triathlon centre, and that it could be a really good thing. Malcom said he was very open to having an endurance centre there – because fortunately it was the same Malcom Brown! – and he said he had some other priorities and work to sort, but so it came to be.

“Leeds Beckett actually put some money in, and British Triathlon put some money in, and so we established a small performance centre based in Leeds.”

There was still one further hurdle for Maitland to overcome, before putting into place the idea he and Simon Ward had proposed.

As the saying goes, Rome wasn’t built in a day, but in the case of the Leeds Triathlon Centre, it almost never got ‘built’ at all.

“I had to interview to get the job – there was a worldwide search for the role – and some excellent people applied, and so it wasn’t a formality that I got the job, but I did.”

“It started off very small scale at first, with four athletes on TASS Funding [Ed. Talented Athlete Scholarship Scheme], plus a few Juniors who were in our programme but still at school, like Alistair, Philip Graves, Vicky Graves and Jonny of course. They would come into the centre once a week for a run session, strength and conditioning, and then that expanded as they went to sixth form and had a little more flexibility.”

That was Autumn 2004 that we got that going, and it continued until 2007 when British Triathlon shut the whole thing down…

Redundancy – down, but not out

If triathlon is a sport which rewards consistency and resilience, then that was happening in the coaching arena too, with Jack not ready to throw in the metaphorical towel, just yet:

“It was all to do with sports politics further up the line, as UK Sport wanted a focus on Beijing [2008 Olympics], and they felt that some of the money that should be going to the Senior athletes was being used to run pathways that they felt should be funded by Sport England. Anyway, the outcome of it was that I got made redundant.

“Even the regional squads got closed down too, because we were deemed not to have any Senior athletes. Of course, we didn’t at the time… but the irony is that Alistair did indeed make the team for Beijing!”

“Jonny and I actually ended up going to Beijing too via an initiative from the British Olympic Association, where they sent a couple of athletes and a coach from each sport to experience the Olympic cauldron with the idea that would better prepare them for the future. It was a great idea.

“British Triathlon’s idea was to centralise everything in Loughborough at the time, but our athletes didn’t want to go there.

“The university liked what we had been doing, so they wanted to keep the activity in Leeds. They put a bit more money in, I took on some more private work, so basically we just kept going with limited British Triathlon support.”

If Alistair’s 2008 selection had perhaps provided the early signs of proof-of-concept of what Jack was trying to build in Leeds, the results of the next decade more than emphasised that the ‘just keep going’ approach has provided an incredible return on investment in medal terms since.

“It took time to build up from that point, but by the time we got to 2012, we had Alistair and Jonny in the team. Malcolm by that stage had done his first retirement from the university job and had got more involved in coaching and directing triathlon. That all went to plan in the 2012 Olympics.

“Then post 2012, the likes of Vicky Holland, Lucy Hall and Mark Buckingham moved to Leeds to join us, alongside Non Stanford, Tom Bishop and Georgia Taylor-Brown, and British Triathlon had been brought then back on side by that stage.”

A glittering legacy

“By the time I left in 2017, we had four squads, 70 athletes and numerous coaches and people performing across the whole width of the triathlon universe really – male and female. I always had an eye on that, as I felt there needed to be a balance in the squad at all levels, including developing female coaches.

“It’s perhaps a little different now because of the Mixed Team Relay, but until a few years ago it was quite unusual to have particular countries or coaches, have significant success both male and female within the same programme.

“We actually managed that fairly well I felt, which I think set us up well for the MTR.”

While Jack left his role at the Leeds Triathlon Centre in Leeds, he is still heavily involved in coaching at the top level.

In the third part of this series, we’ll pick up the story of how he helped Beth Potter transition from Rio 2016 Olympian over 10,000m, to World Triathlon champion in 2023.

Jack Maitland interview series links:

- Part One: Jack Maitland’s journey into swim/bike/run

- Part Two: How Leeds Triathlon Centre went from idea to glittering reality

- Part Three: Beth Potter’s rise from triathlon novice to World Champion